By Robin F. Goodman, Ph.D.

Introduction

Not that long ago, students would be sent to the principal’s office as the ultimate penalty for breaking a rule, or in extreme cases, breaking the law. Nowadays however, discipline in schools is more complicated. In response to the current fear of school-related violent incidents, many schools have recently enacted what are called "zero tolerance (ZT) policies." This term is commonly used to describe "a school discipline policy enacted by school officials that specifies a mandatory and strict punishment for engaging in activity that officials deem intolerable" usually with respect to guns, drugs, and violence. (The Rutherford Institute)

Background

The well-publicized school shootings over the past years have heightened awareness of violence in schools and alarmed parents and professionals. Those feeling responsible have been left questioning what more they could have done to avoid tragedy. ZT policies represent an attempt at prevention, intervention, and avoidance of blame. The cry to do more is based on the belief that students, teachers, and parents need to feel safe to go about the business of education. Certainly schools and communities feel increasing pressure to have clear, strict rules that can be applied indiscriminately. Yet schools also hear the outrage if the policies are applied in too harsh a manner. Determining the most effective solutions means facing some difficult realities, making hard choices, but acting with compassion.

In the News

Four kindergarten children were suspended for three days after pointing their fingers at each other while playing cops and robbers. (The Patriot Ledger, April 18, 2000).

A fourth grader has been suspended and ordered to undergo a psychological evaluation after telling a classmate he was going to "shoot" another student with a wad of paper launched form a rubber band. (The New York Times, April 27, 2000).

A girl is booted out of school for 10 days in 1997 for chucking into her backpack a butter knife she had used to pry lunch money out of her piggy bank. (The Morning Call, January 23, 2000).

A Pennsylvania school’s zero-tolerance policy that mandated a one-year suspension for students who bring weapons to school, was ruled unconstitutional. The verdict exonerated a 12-year-old student who was suspended for one year for filing his nails with a Swiss Army knife he found in a school hallway…[the judge] wrote that the policy "frustrates the clear legislative intent that this statute not be blindly applied."

Unpublicized facts

The Justice Policy Institute has reported on the disparity between public fear and actual crime statistics.

49% of Americans polled by USA Today immediately after the Columbine shooting said they feared school shootings more than they had the year before. But school-associated violent deaths actually fell 40% in the 1998-99 school year compared with the year before.

The odds of a child dying at school remain one in 2 million, according to the National School Safety Center. But 71% of people answering a 1998 NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll said they thought it likely that a school shooting could take place in their community.

According to the Department of Special Education at the University of Maryland, students at schools having "secure building" strategies to fit crime such as metal detectors and locker searches were more likely to be fearful and victimized than those in schools with less restrictive school safety measures.

(Justice Policy Institute, Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice)

Are an ounce of prevention and a pound of cure the same thing?

Do ZT policies prevent violence or alter the climate of fear in schools and the mind of the public? Would their existence have changed the course of history for any of the most recent horrific school events? Yet to be determined is if and how ZT policies can effect positive outcomes. In fact, we may be creating a more serious problem.

• The fear driven ZT policies with mandatory expulsion may be responsible for the increase in suspensions from 1.7 million in 1974 to 3.1 million by 1997 (Department of Education Office for Civil Rights).

• A spiraling effect exists in that youths out of school are more likely to get involved in physical fights and to carry weapons, smoke, use alcohol, marijuana and cocaine, engage in sexual intercourse, have poor eating habits (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

The narrow focus on violence negates the more pervasive problems of peer pressure, bullying, family, learning, and mental health problems. In the aftermath of many of the school shootings we have learned of the children’s different types of troubling backgrounds. "Children just don’t snap and go on shooting sprees. Children who commit violent acts almost always have histories of aggression, or other mental problems" (Koplewicz, 1999). No one policy can address all these issues simultaneously but policies should consider the larger context in which all child and teen behavior occurs.

What parents and educators can do

Although ZT policies stem from a need to provide guidance, establish responsible standards and restore order in school settings, the potential risk is that ZT policies address the punishment phase of the problem exclusively. It would be unfortunate if the intent of ZT policies was lost amidst the struggle to find the right balance between their standards and reasonable individualized interpretation. Research and practical experience have taught us that, especially where young children are concerned, punishment alone is never the most effective strategy for promoting change. The best policies are those included in a comprehensive approach. The best results will be achieved when we:

1. understand the motivation for the behavior

2. consider the individual(s) involved

3. assess any underlying mental illness

4. have multi-system involvement, including the child, family, school, outside community resources

5. educate youngsters about being responsible for themselves and each other

6. destigmatize mental illness

7. incorporate common sense

8. increase and improve child mental health services

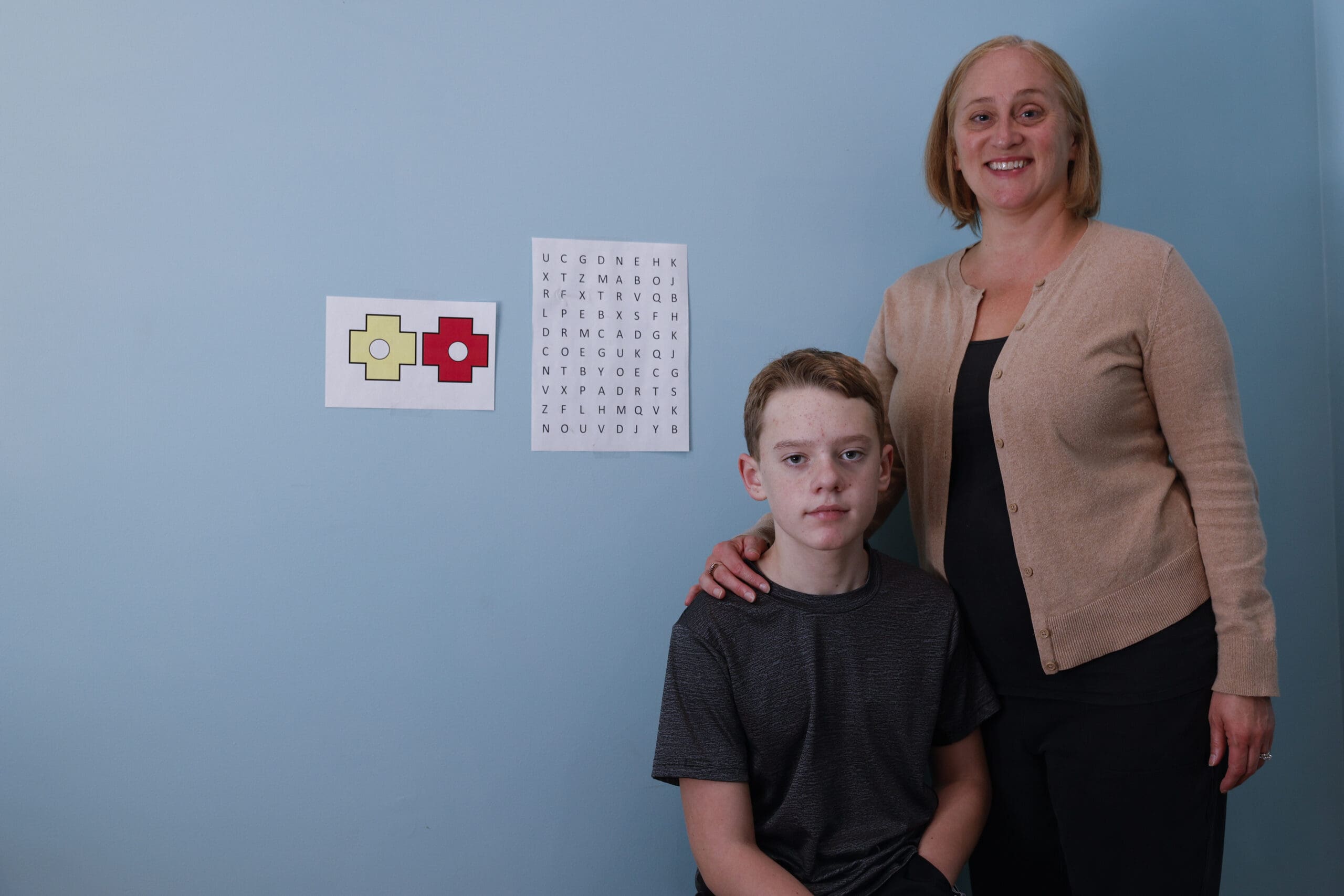

With close to 15 million children and teens having a mental illness or substance abuse problem, but only 20% getting help, it’s clear that child mental health issues are not effectively recognized or adequately treated. In addition to zero tolerance, schools should have open mental health doors. One recent study "found only 11% of students referred by their schools for mental health consultation in a community clinic ever made it to their first appointment. But more than 90% made it if there was a mental health clinic right in school" (Koplewicz, 1999). No one person or sector of society should bear the full burden of responsibility for addressing child mental health needs. However, better access to mental health services, elimination of myths, and removal of obstacles will help pave the way.

About the Author

Robin F. Goodman, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist specializing in bereavement issues.

The NYU Child Study Center is dedicated to to the understanding, prevention, and treatment of child and adolescent mental health problems. For more information visit AboutOurKids.org.