By Anita Gurian, Ph.D.

The upsides of friendships are considerable and start early. Humans are born social, and even babies reach out for contact. During the toddler years, social interaction flourishes in the playground, child care settings, and preschool programs. As their world expands children are constantly interacting with peers in school, teams, clubs, and other groups. Although friendships do not supplant the warmth and intimacy of family, they provide opportunities to learn how to get along with others, to make decisions in different situations, and to enjoy the companionship of others. Friendships provide deep and satisfying life experiences which build self-esteem and self-confidence.

Friendships change over time

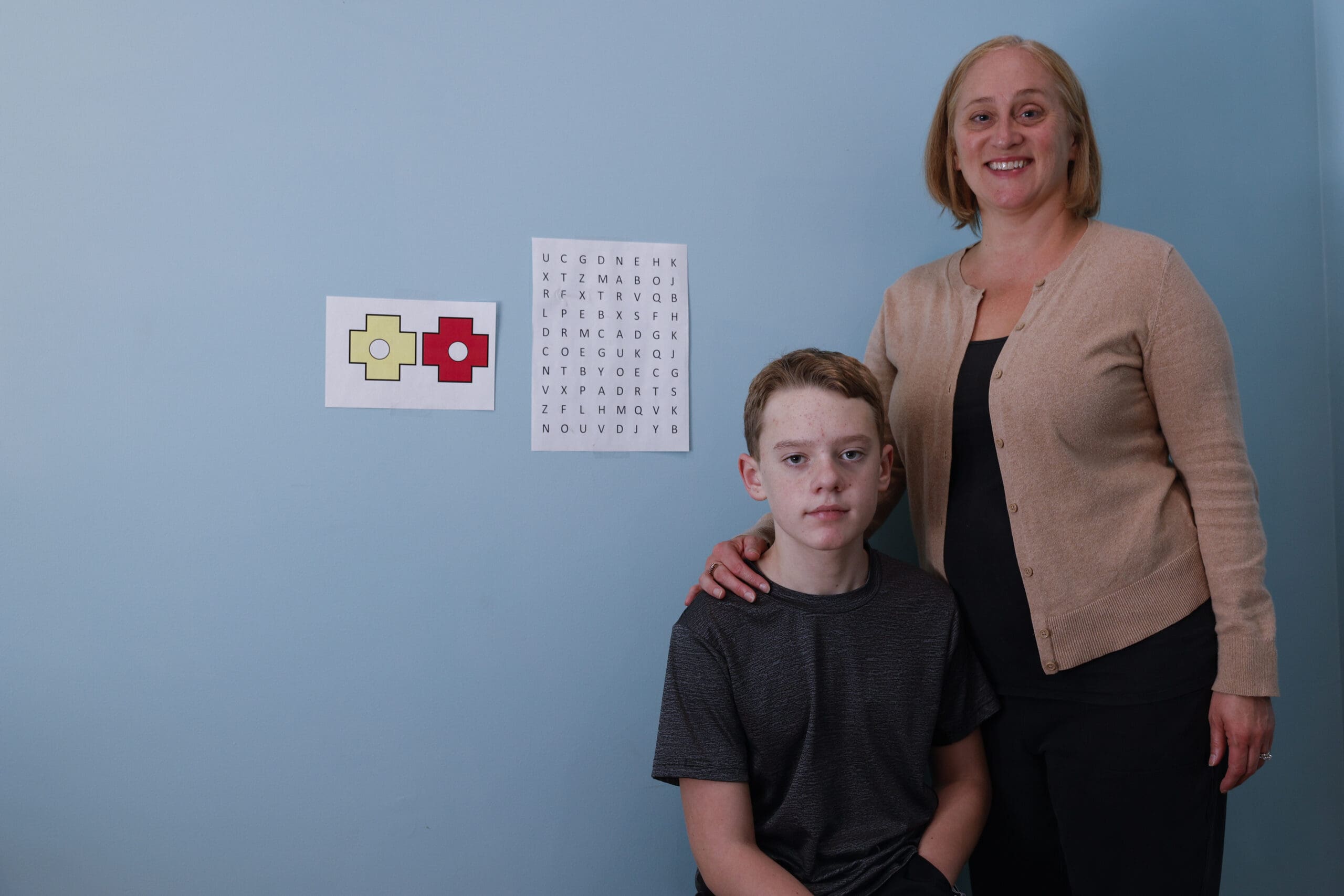

In the early and middle years, activities are often planned and supervised, so parents can easily decide who their children see and don’t see. In middle school demands change—children have to manage themselves, social relationships are more complex, and the pressure to be like everyone else escalates. By the teen years parents are not their children’s only influence and they have less control over their children’s friendships. As teenagers struggle to become more independent, it’s natural for them to bond with peers, and many teenagers are closer to their friends at times than to their families.

Although peer pressure starts early, it intensifies in middle and high school when peers influence the music teens listen to, the clothing they wear, and the activities they take part in—studying for a test, practicing a sport, volunteering for a community service project, the list is long. But some teenagers, while exploring and learning about themselves, may be attracted to peers that parents may be concerned about.

When friendship has a downside

Peer pressure, although positive for many teens, can also have a negative impact. If a teen admires another teen or group whose behavior he thinks is "cool," he may be distracted from constructive activities such as completing homework, trying out for a team, respecting speed limits and drinking laws, and be swayed to break rules or try risky behaviors. Teens who have a history of difficult behavior and poor relationships with their peers can be attracted to other teens with antisocial or delinquent behavior.

What parents can do

Helping children learn to deal with peer pressure and competition is more important than protecting them from it. There are many ways in which parents can indirectly influence their children’s choice of friends.

• Continue or establish the custom of family meetings. Always let your children know you support them and are proud of their accomplishments. From time to time repeat what you mean by "acceptable behavior". Talk about many topics—tobacco, drinking, illegal drugs, driving, sex, respect for property, cheating, and other choices teens have to make. Plan regular and frequent whole family activities—picnics, hikes, sports. If a close and trusting family relationship has been established, teens are more likely to come to their parents when they’re in trouble or have problems.

• Pick your battles—don’t make an issue about a temporary and harmless issue like clothes and music; leave the objections to things that really matter like the use of tobacco, drugs, and alcohol. Respect your child’s privacy, unless you see signs of serious trouble.

• Encourage friends to spend time at your house where you can be aware of their activities and interests. Get to know your child’s friends and their parents. Point out what you like about them. Encourage diverse friendships that expose your child to new interests and ideas. Encourage children to get involved in activities that will attract others with similar interests—sports, theater groups, music, art, chess clubs, volunteer activities.

• Establish appropriate house rules:

• Know where your teens are going, who they’re going with, and when they’ll be home

• Specify the consequences of breaking rules

• Set time limits for television and computer time

• Be aware of who your child is contacting on the internet

When you’re concerned about your child’s friendships

Allowing an objectionable friendship to run its course will often work better than trying to stop it. Many of the friendships parents worry about turn out to be short-lived. Often a teen will discover that a friend he admired at first wasn’t so terrific after they got to know each other better.

If you have concerns about a friend, express them openly and listen to your child’s point of view. Don’t criticize friends directly; but discuss specific behaviors. For example, "It seems that every time XX is over, the rules about using the computer are broken." Forbidding contact seldom works and can reinforce the friendship; however, limiting the opportunities for contacts can be effective. If you are concerned about a particular friend, think about the need that the friendship seems to fill. Ask your child what he likes about the friend, and talk about the qualities that make a good friend.

If you dislike your child’s friend, ask yourself some questions as to the possible reason: Do I dislike the child or his appearance? Is the child from another social, ethnic or religious background? Do I allow my child’s opinions to differ from my own?

Teach assertiveness and role-play different ways of saying no

Because it’s easier for a teen to go along with the group if she feels unsure of herself, bolster her self-confidence by teaching her to make her own decisions. For example, discuss some hypothetical choices about fitting in with the crowd and a) breaking the rules about driving or b) saying no or finding another way to have fun with friends. The following steps can be helpful in practicing decision making skills:

• Identify what needs to be decided

• Gather the information necessary including possible solutions or alternatives

• List the possible courses of action

• Think aloud about the consequences of poor choices: disappointing parents, getting grounded, being in a car crash, unwanted sex, getting involved with the law. Each individual must realize that the choice is theirs—not their peers.

• Review and reinforce the concept that she can make her own choices, that she has the courage to refuse to go along with the crowd when their behavior conflicts with her values.

Be aware of warning signs of trouble

Parents have to distinguish between experimentation and danger. When potentially dangerous situations are involved, such as when the child aligns himself only with others who are belligerent or who engage in antisocial or delinquent acts, parents have a responsibility to discourage the association. When behavior is dangerous it must be stopped.

Be aware of the warning signs that indicate that consultation with a mental health professional may be helpful, such as: extreme weight change; sleep problems, drastic personality change, skipping school, poor academics, talk of suicide, signs of substance use, run-ins with the law.

The NYU Child Study Center is dedicated to the understanding, prevention, and treatment of child and mental health problems. For more information visit

aboutourkids.org.