By Karla Robinson, MD

Dehydration is one of the most common heat-related illnesses that we are faced with in the summer months. With temperatures soaring well into the 90 degree mark, and heat indices over 100 degrees, many people are at risk for complications from the heat.

Some common symptoms of dehydration include dry mouth, fatigue, increased thirst, and headache. If the loss of fluids continues and the heat-related dehydration is not caught in its early stages, the symptoms may progress to heat exhaustion or the potentially fatal heat stroke.

Heat exhaustion can occur once the body temperature rises and it is not able to cool itself sufficiently by sweating. There is often a loss of fluids and electrolytes (i.e. sodium, and potassium). Common symptoms include nausea and vomiting, fatigue, weakness, muscle cramps, and dizziness.

Heat stroke occurs once the core body temperature reaches 105 degrees or higher. These symptoms can sometimes occur suddenly or with little warning. They include loss of sweating, increased heart rate, confusion, disorientation, seizure, coma, or ultimately death. It is always necessary to seek immediate medical attention if heat exhaustion or heat stroke is suspected. Until evaluated by a medical professional, attempt to cool the person by removing all clothing and applying cool water to the skin.

The elderly are particularly at risk for dehydration for a variety of reasons. In addition to an often long list of medical conditions including high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, those who are 65 years and older have a much more difficult time with body temperature regulation. There are often medications commonly used in the elderly population that can lead to an increased risk for dehydration. These may include some blood pressure medications, antihistamines, laxatives, and diuretics.

There are often many hindrances that keep the elderly from getting the adequate amount of fluids needed to prevent dehydration. In addition to their decreased ability to recognize thirst, the elderly may also have health conditions limiting their mobility and preventing them from readily getting to the fluids they may need.

Sweating, the natural mechanism the body has to cool itself, may also be impaired. The elderly are often prone to having a decreased number of sweat glands. Additionally, the sweat glands that remain tend not to function as well, making it even more difficult for the body to cool itself when overheated.

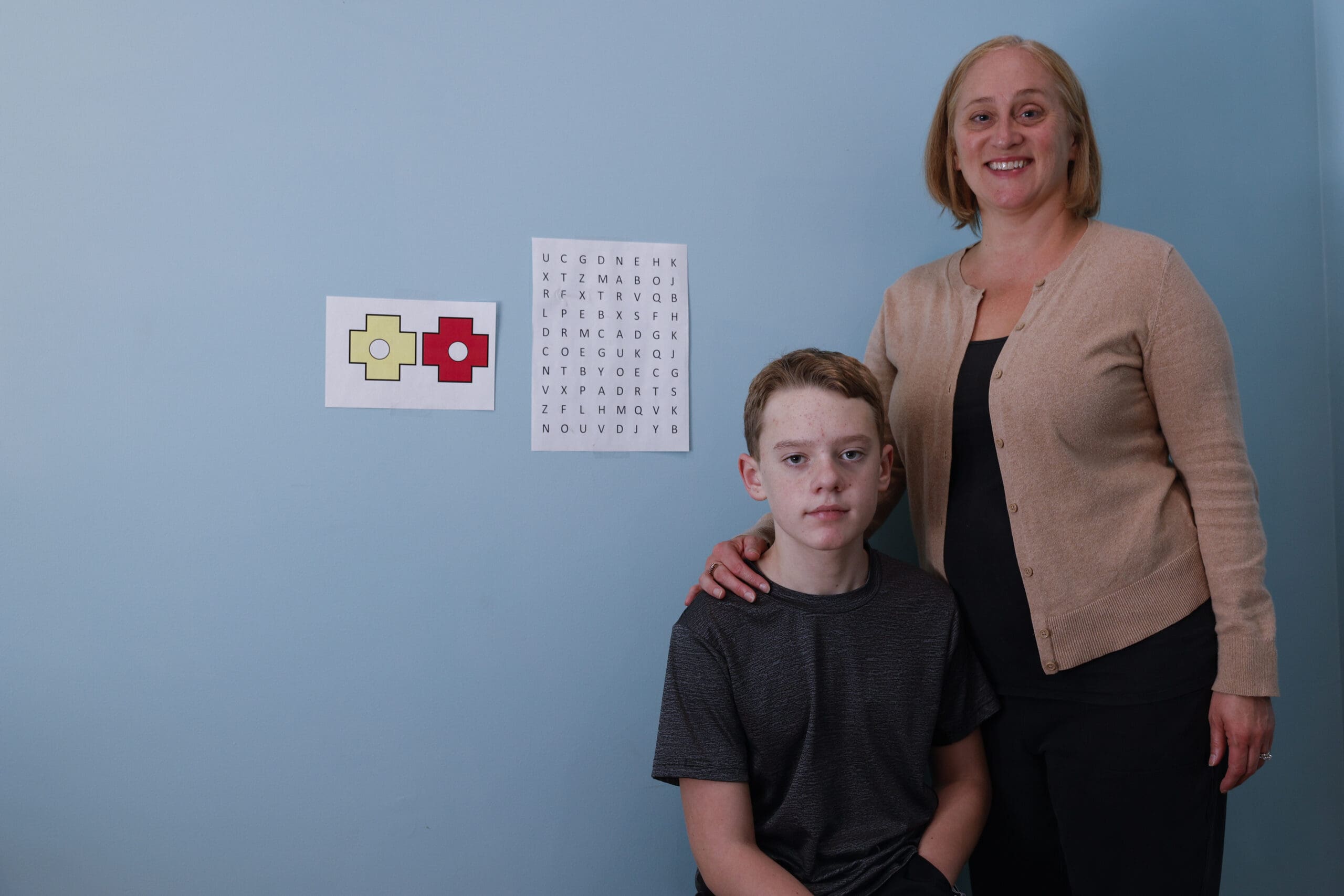

Children are also vulnerable to dehydration, as they generally produce less sweat, reach much greater body temperatures, and are less prone to drink enough fluids to replace those that may be lost during the heat. This can be particularly challenging for young athletes in sports camps training in the summer. Other symptoms of heat related illness in

young athletes include severe muscle cramps. These can often occur after the training or physical exertion has been completed. Those children at an even greater risk for dehydration include overweight or obese kids, those kids who may rarely exercise, and those who may have had a diarrheal or vomiting illness that may have predisposed them to an overall fluid loss recently.

It is always safest to stay indoors and avoid strenuous activities in the extreme heat. However, if you find yourself outdoors during high temperatures, try to combat the summer heat by following these tips:

• Know the signs. Make sure to keep your family safe by discussing the subtle symptoms of dehydration. Acting quickly can prevent the devastating

complications of heat-related illnesses.

• Quench thirst wisely. Alcoholic and caffeinated beverages can contribute to fluid loss and worsen dehydration. When choosing a beverage to quench the summer thirst, avoid drinks containing alcohol or caffeine. Water is better.

• Restore and replete. Replenishing fluids that may be lost in the heat is the key. Keep water and/or electrolyte replacement sports drinks on hand when

outdoors this summer. An average of two to four 8 ounce glasses of water per hour will effectively prevent dehydration in extreme heat.

• Rest and recharge. Frequent breaks are highly encouraged when participating in any sort of physical activity in the summer heat. Take the time to recharge and avoid overexertion..

Myths about heat stress

There are many misconceptions about heat stress, heat illnesses, and what a person should do when they are required to work hard in a hot environment.

MYTH: The difference between heat exhaustion and heat stroke is there is no sweating with heat stroke.

Exertional heat stroke victims may continue to produce sweat If a worker is experiencing symptoms of heat stroke (confusion, loss of consciousness, seizures, high body temperature), whether they are sweating or not, it is a life-threatening emergency! Call 911 and try to cool the worker down.

MYTH: Salt tablets are a great way to restore electrolytes lost during sweating.

Salt tablets should never be used unless a worker is instructed to do so by their doctor. Most people are able to restore electrolytes through normal meals and snacks. Workers should drink plenty of water with their meals and snacks, not only to stay hydrated but also to aid digestion. Moreover, ingestion of too much salt may cause nausea and vomiting which can worsen the level dehydration already present.

MYTH: My medications/health condition will not affect my ability to work safely in the heat.

A worker’s health and medication usage may affect how their body handles high temperatures and heavy physical exertion. Some health problems that may put a worker at a greater heat illness risk include: obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even common colds and the flu—especially if the illness is accompanied by a fever and vomiting. Certain medications may affect the body’s ability to cool down or may cause the body to heat up more quickly. Workers with health conditions or who are taking medications should discuss with their physicians about how they may be at additional risk if working in a hot environment.

Source: CDC

This was printed in the July 1, 2012 – July 14, 2012 Edition