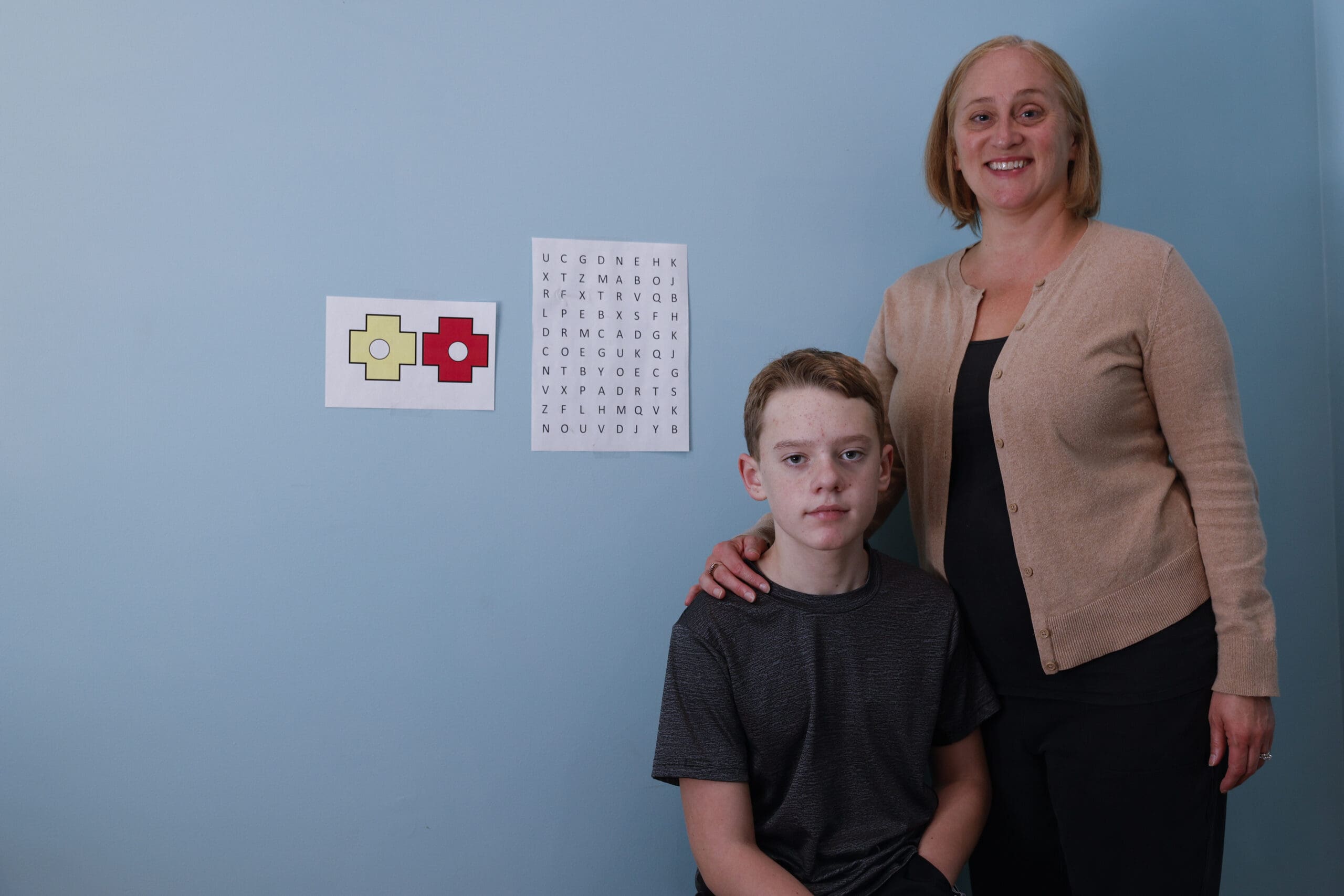

EAST LANSING, MI — Mothers who took on burdensome caregiving roles as children — and weren’t allowed to just “be kids” — tend to be less sensitive to their own children’s needs, finds new research led by a Michigan State University scholar.

EAST LANSING, MI — Mothers who took on burdensome caregiving roles as children — and weren’t allowed to just “be kids” — tend to be less sensitive to their own children’s needs, finds new research led by a Michigan State University scholar.

The findings suggest these parents do not understand appropriate child development and end up parenting in a similar harmful manner in which they were raised. The study is online now in advance of print publication in the Journal of Family Psychology.

“If your childhood was defined by parents expecting you to perform too much caregiving without giving you the chance to develop your own self-identity, that might lead to confusion about appropriate expectations for children and less accurate knowledge of their developmental limitations and needs as infants,” said Amy K. Nuttall, assistant professor in MSU’s Department of Human Development and Family Studies and lead author on the study.

“If mothers don’t understand their children’s needs,” Nuttall concluded, “they’re not able to respond to them appropriately.”

Burdensome, adult-like caregiving, or “parentification,” can involve routine parenting and disciplining of one’s siblings, excessive chores and responsibilities around the house, and serving as the main emotional support system for parents.

For the study, 374 pregnant women from low-income households in four U.S. cities were surveyed about their upbringing. After birth, the mothers’ parenting techniques were observed several times during an 18-month period.

Mothers who engaged in excessive, adult-like caregiving as children were less likely to respond warmly and positively to their infant’s needs and interests and to put their child’s need for exploration and independence over their own agenda.

A previous study led by Nuttall, which also appeared in the Journal of Family Psychology, found the children of mothers who engaged in excessive caregiving during childhood went on to display behavioral problems. Together, the studies have important implications for developing parent-education programs for mothers who were overburdened by caregiving roles in childhood.

Nuttall said instruction about infant development might be best served in prenatal classes. Women are more likely to attend prenatal classes than parenting classes offered after birth.

“Prenatal parenting classes may be particularly useful for teaching accurate knowledge of child development and appropriate expectations about children’s abilities even before mothers give birth and begin parenting,” Nuttall said.

Her co-authors are University of Notre Dame researchers Kristin Valentino, Lijuan Wang, Jennifer Burke Lefever and John Borkowski.

For MSU news on the Web, go to MSUToday. Follow MSU News on Twitter at twitter.com/MSUnews.

This was printed in the October 17, 2015 – October 31, 2015 edition.