<script type="text/javascript" src="http://pixel.propublica.org/pixel.js" async="true"></script>

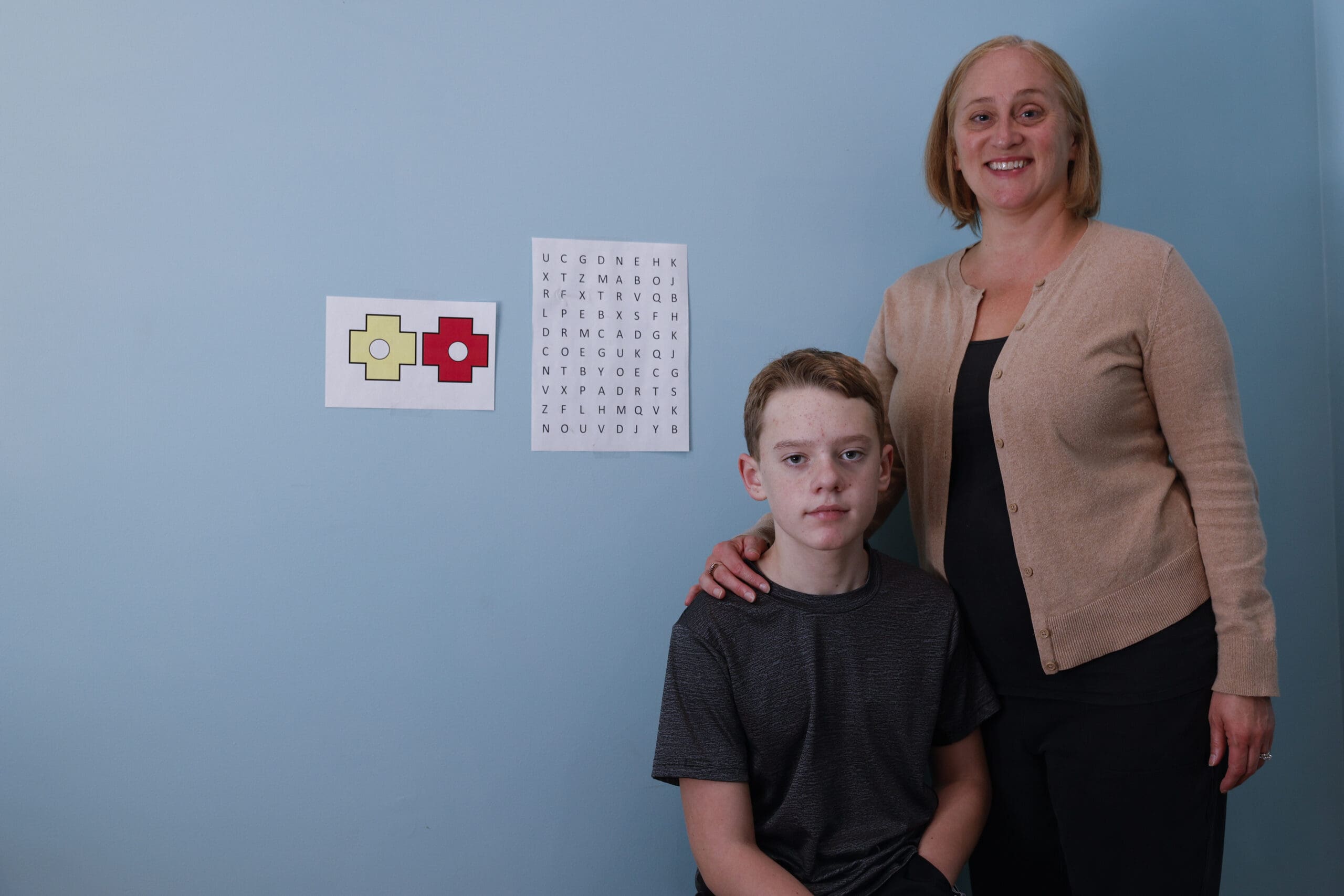

(Andres Cediel/FRONTLINE)

(Andres Cediel/FRONTLINE)

By A.C. Thompson, Mosi Secret, Lowell Bergman and Sandra Bartlett

Watch Frontline’s documentary produced in conjunction with this story. And listen to NPR’s All Things Considered for more on this story.

Feb. 4: This post has been corrected .

In detective novels and television crime dramas like “CSI,” the nation’s morgues are staffed by highly trained medical professionals equipped with the most sophisticated tools of 21st-century science. Operating at the nexus of medicine and criminal justice, these death detectives thoroughly investigate each and every suspicious fatality.

The reality, though, is far different. In a joint reporting effort, ProPublica, PBS “Frontline” and NPR spent a year looking at the nation’s 2,300 coroner and medical examiner offices and found a deeply dysfunctional system that quite literally buries its mistakes.

Blunders by doctors in America’s morgues have put innocent people in prison cells, allowed the guilty to go free, and left some cases so muddled that prosecutors could do nothing.

In Mississippi, a physician’s errors in two autopsies helped convict a pair of innocent men, sending them to prison for more than a decade.

The Massachusetts medical examiner’s office has cremated a corpse before police could determine if the person had been murdered; misplaced bones; and lost track of at least five bodies.

Late last year, a doctor in a suburb of Detroit autopsied the body of a bank executive pulled from a lake — and managed to miss the bullet hole in his neck and the bullet lodged in his jaw.

“I thought it was a superficial autopsy,” said David Balash, a forensic science consultant and former Michigan state trooper hired by the Macomb County Sheriff’s Department to evaluate the case. “You see a lot of these kinds of things, unfortunately.”

More than 1 in 5 physicians working in the country’s busiest morgues — including the chief medical examiner of Washington, D.C. — are not board certified in forensic pathology, the branch of medicine focused on the mechanics of death, our investigation found. Experts say such certification ensures that doctors have at least a basic understanding of the science, and it should be required for practitioners employed by coroner and medical examiner offices.

Yet, because of an extreme shortage of forensic pathologists — the country has fewer than half the specialists it needs, a 2009 report by the National Academy of Sciences concluded — even physicians who flunk their board exams find jobs in the field. Uncertified doctors who have failed the exam are employed by county offices in Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania and California, officials in those states acknowledged. Two of the six doctors in Arkansas’ state medical examiner’s office have failed the test, according to the agency’s top doctor.

In many places, the person tasked with making the official ruling on how people die isn’t a doctor at all. In nearly 1,600 counties across the country, elected or appointed coroners who may have no qualifications beyond a high-school degree have the final say on whether fatalities are homicides, suicides, accidents or the result of natural or undetermined causes.

For 26 years, Tim Brown, a construction manager, has served as the coroner of rural Marlboro County in South Carolina, a $14,000-per-year part-time post. “It’s been kind of on-the-job training, assisted by the sheriffs,” he said.

Long before the current economic crisis began shrinking state and county government budgets, many coroner and medical examiner offices suffered from underfunding and neglect. Because of financial constraints, Massachusetts has slashed the number of autopsies it performs by almost one quarter since 2006. Oklahoma has gone further still, declining to autopsy apparent suicides and most people age 40 and over who die without an obvious cause.

Some death investigation units do a commendable job. While many coroners and medical examiners don’t even have X-ray machines, New Mexico has a new facility equipped with a full-body CT scanner to help detect hidden injuries. Virginia has an efficient, thorough system, staffed by more than a dozen highly trained doctors. The autopsy suite in its Richmond headquarters is as sophisticated and sanitary as a top hospital.

Still, the National Academy of Sciences’ study found far-reaching and acute problems. Across the country, the academy said, coroners and medical examiner offices are struggling with inadequate resources, poor scientific training and substandard facilities and technology.

Their limitations can have devastating consequences.

“You call a death an accident or miss a homicide altogether, a murderer goes free,” said Dr. Marcella Fierro, Virginia’s former chief medical examiner and one of the report’s authors. “Lots of very bad things happen if death investigation isn’t carried out competently.”

A Series of Errors and Oversights

After Cayne Miceli died in January 2009, her body was brought to the New Orleans morgue, a dingy, makeshift facility in a converted funeral home, for Dr. Paul McGarry to autopsy.

Dr. Paul McGarry (Photo courtesy of Frontline)

Dr. Paul McGarry (Photo courtesy of Frontline)

An autopsy, the dissection and evaluation of a corpse, generally begins with a physician scrutinizing the body, noting visible injuries. With a scalpel, a doctor then slices a long, Y-shaped incision in the torso and studies the innards, removing and weighing each organ, and using a small rotary saw to remove the top the skull. An autopsy can trace the path of a bullet through a body, or reveal microscopic damage to blood vessels in the brain, or identify a lethal clog in an artery.

By the time Miceli’s body was laid on the stainless-steel examination table, McGarry had performed such work for three decades in Louisiana and Mississippi. In New Orleans, he was one of several forensic pathologists overseen by the parish coroner, Frank Minyard, a trumpet-playing local legend who has held his elected office for more than 35 years.

Miceli, 43, had died after being held in a cell in the parish jail, bound to a metal bed by five-point leather restraints. During the autopsy, McGarry observed “multiple fresh and recent injection sites” on Miceli’s forearms. He determined that drugs — he didn’t specify the variety — had killed her, according to his report.

But doctors who had treated Miceli the day she died encouraged her father, Mike Miceli, to look more closely into his daughter’s death. He had her body flown to Montgomery, Ala., for a second autopsy by Dr. James Lauridson, the retired chief medical examiner for the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences.

Lauridson concluded that McGarry had misconstrued the needle marks on Miceli’s arms. “In fact, all of the needle puncture marks were therapeutic — drawing blood, IV’s, that sort of thing,” Lauridson said.

McGarry’s finding also was contradicted by a central piece of evidence: a screen for drugs and alcohol didn’t turn up either in Miceli’s blood. McGarry had reached his conclusion days before he got the test results, records show.

Lauridson soon pinpointed the real reason for Miceli’s demise. On the day of her death, Miceli had gone to the hospital to be treated for an asthma attack. She was arrested after an altercation with hospital staffers; Miceli thought they were trying to discharge her too soon, court records show. Peering at Miceli’s lung tissue under a microscope, Lauridson was certain that severe asthma, combined with the way she was restrained at the jail, had caused her death.

“As I examined her lungs, it was very clear right away that her lungs and all of the airways were completely filled with mucous,” he said. “To put an asthmatic flat and then tie them down during an acute asthma attack is nearly the same as giving them a death sentence.”

Mike Miceli (Photo courtesy of Frontline)

Mike Miceli (Photo courtesy of Frontline)

McGarry had been wrong, and not for the first time. In fact, a review of medical records, court documents and legal transcripts shows McGarry has made errors and oversights in autopsy after autopsy.

In three instances since 2005, his findings in cases in which people died in the custody of police officers have been challenged by doctors brought in to perform second autopsies. In each case, McGarry’s findings cleared officers of wrongdoing. The other specialists concluded the deaths were homicides.

Contacted by phone, mail and in person, McGarry repeatedly declined to comment for this article or related radio and television stories.

Some in the field champion McGarry, praising his track record. “I have the utmost respect for Dr. McGarry and he taught me much when I was in a forensic fellowship program,” said Dr. James Traylor in an e-mail. Traylor was trained by McGarry and worked alongside him in the New Orleans morgue. “I am unaware of any ‘mistakes’ that he may have made.”

Second autopsies are a rarity in most jurisdictions, but New Orleans civil rights attorney Mary Howell said she often taps forensic pathologists to perform follow-ups when she knows McGarry has handled a case. The degree to which their findings have differed from McGarry’s is “shocking,” Howell said. In some cases, they discovered, McGarry’s work was so incomplete that bodies were “half-autopsied.”

Gerald Arthur, a 45-year-old construction worker with a history of drug arrests, died after a struggle with police on a New Orleans street in 2006. Based on McGarry’s findings , coroner Minyard ruled the death an accident, but a forensic pathologist with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation brought in by Arthur’s family to perform a second autopsy found four broken ribs that McGarry had not noted. In his report , the GBI pathologist also stated that McGarry “failed to dissect” key neck muscles, causing him to miss hemorrhages that, in his view, suggested Arthur had been strangled.

In a deposition, McGarry disputed that assertion, saying he had dissected the neck muscles but had come to a different conclusion. “I don’t have any evidence that this man had a death due to neck strangulation,” he said.

No criminal charges have been brought in connection to Arthur’s death. His family settled a lawsuit against the police department last year for $50,000.

Also in 2006, McGarry autopsied Lee Demond Smith, a 21-year-old man who died in jail in Gulfport, Miss. McGarry decided that Smith had been killed by a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the lungs, based on evidence of internal bleeding. Again, another specialist brought in to do a second autopsy found injuries that McGarry had not: abrasions on Smith’s forehead and chest, as well as a half-dozen bruises on his legs and hands. The doctor concluded that Smith, like Arthur, had been strangled.

No criminal charges have been filed in Smith’s death either.

Raymond Robair, a 48-year-old handyman who died shortly after an encounter with police, was autopsied by McGarry in 2005. Based on McGarry’s examination, coroner Minyard declared Robair’s death an accident.

But McGarry had not noted the wounds covering Robair’s legs and arms. A second forensic pathologist hired by Robair’s family documented 23 separate bruises, including a thigh contusion more than a foot long. The fatal injury was a severe laceration of Robair’s spleen that caused extensive internal bleeding, according to the second autopsy, which was performed by another GBI doctor, Kris Sperry. Robair “was the victim of a beating,” his autopsy report states.

Robair’s sister, Pearl LeFlore, said her sibling’s battered body was communicating a message: “This is what happened to me. … I died brutally. I was beaten.” McGarry’s autopsy was “a lie altogether,” she said.

Based on McGarry’s autopsy, records show, the district attorney’s office decided not to prosecute any police officers in connection with Robair’s death. “The officers were effectively exonerated by the initial autopsy performed by the Orleans Parish Coroner’s Office,” wrote an assistant district attorney in a 2008 letter sent to the police department.

Ultimately, in 2010, after conducting an extensive investigation, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted New Orleans Police officer Melvin Williams for allegedly beating Robair to death and charged another officer with allegedly helping to cover it up. The officers have pleaded not guilty.

Cayne Miceli’s father is still seeking justice. Mike Miceli has sued McGarry in Orleans Parish court, saying his actions were “extreme and outrageous,” and has filed a separate suit against the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Department for wrongful death. Both cases are pending.

“There’s no reason for a family to have to go through this,” Mike Miceli said. After the lawsuits were filed, Minyard amended the autopsy report, changing Miceli’s cause of death from a drug overdose to asthma and labeling it a natural death.

Minyard declined to discuss the Miceli autopsy or other cases in which McGarry’s findings have been challenged. He defended McGarry’s work more generally. “I’m not aware of any impropriety,” the coroner said. “I’m not aware of any mistakes.”

Last year, McGarry stopped doing autopsies for Orleans Parish, but he is still working for three Mississippi counties. “He lives in Mississippi, and he’s helping them over there,” Minyard said. “The travel back and forth was too much.”

The Debate Over Coroners

Some experts see coroners like Minyard as throwbacks to an earlier, less scientific era.

The qualifications of those who oversee death investigations vary widely from state to state — and, in some areas, from county to county. But the main divide is between medical examiner systems, run by doctors specially trained in forensic pathology, and coroner systems, run by elected or appointed officials who often do not have to be doctors.

While Minyard happens to be a physician — he worked as an obstetrician-gynecologist before becoming coroner — he isn’t a forensic pathologist and never actually puts scalpel to flesh. In the end, though, it is Minyard who decides what words will be typed on the death certificate.

The 2009 report by the National Academy of Sciences, a comprehensive overview of defects in the nation’s death investigation system authored by more than 50 luminaries in the field, recommended phasing out coroners and replacing them with medical examiners. (For a detailed, state-by-state breakdown, see our app .)

For Fierro, the Virginia forensic pathologist, the coroner-versus-medical-examiner debate is fundamentally about competence. In her view, only trained specialists should oversee death investigations. “I’m not anti-coroner,” said Fierro, one of the authors of the academy’s report. “I’m pro-competency.”

But another concern raised by the academy is that coroners often are closely aligned with law enforcement agencies. In 48 California counties, the local sheriff serves as coroner. In Nebraska, county prosecutors perform the coroner’s duties. “Sensitive cases, such as police shootings and police encounter deaths … require an unbiased death investigation that is clearly independent of law enforcement,” the NAS report stated.

Minyard’s close ties to law enforcement have provoked controversy throughout his long career, and his decisions in certain cases, particularly that of Adolph Archie, illustrate just how much power a coroner can wield.

Archie died in 1990, soon after grabbing a revolver from a Superdome security guard and shooting a police officer to death.

When officers captured Archie, the chatter on the police radio turned sinister. “Somebody kill him,” demanded one cop, according to a transcript of the radio traffic. “Hang the bitch by his balls,” urged another.

By the time Archie reached Charity Hospital, he’d suffered a host of injuries, including broken facial bones and skull fractures, leading hospital staffers to conclude he had been kicked repeatedly, medical records show.

McGarry did the autopsy, noting many of Archie’s injuries. Minyard initially told the media he was baffled and didn’t know whether to rule the death a homicide. He speculated that Archie might have fallen backward and hit his head on the floor when he struggled with officers, or that officers might have struck him in self-defense.

“When a perpetrator grabs a gun, a policeman has a right to defend himself,” Minyard told the local newspaper.

Media reports later revealed that one of the officers who arrested Archie was a friend of Minyard’s who rented an apartment from the coroner.

A second autopsy conducted by Sperry, the Georgia doctor, uncovered additional injuries overlooked by McGarry, including more skull fractures, crushing damage to Archie’s larynx and bruising of his testicle. After public protests calling for the coroner’s resignation, Minyard changed his determination, calling Archie’s death a homicide.

Then he shifted his stance again, deciding that Archie had died of an allergic reaction to medication he received in the hospital. To this day, Minyard insists Archie wasn’t killed by a police beating. “His trauma never caused his death,” said the coroner, adding that “my position was that Adolph Archie died from an allergic reaction to iodine that he was given on the X-ray table.”

Prosecutors never indicted anyone in connection with Archie’s death.

“I don’t think there’s anybody in town who doesn’t believe that he was beat to death by the police,” said Mary Howell, the civil rights attorney who represented Archie’s children in a wrongful-death suit. The city of New Orleans paid $330,000 to settle the case. From Howell’s perspective, the Archie story — and Minyard’s role in it — sent an “extremely damaging message.”

“That was kind of a watershed incident in this city,” she said.

Minyard believes criticism of coroners is “malarkey” — in fact, he doesn’t believe coroners even need a high-school diploma to do the job.

“Being a good coroner involves a lot more than finding out a cause of death,” he said, adding that the key skills are the ability to speak to grieving families and to the media. “It has nothing to do with education. It has to do with you as an individual and the love that you have for your fellow man. And so that’s why I say having a coroner who has no education sometimes is better than a medical examiner who has all of the education in the world.”

Several of the country’s most esteemed death-investigation units are overseen by coroners, including the coroner’s office in Clark County, Nev., which was the model for the TV show “CSI.”

P. Michael Murphy, a former police chief, is the coroner there. He thinks the national academy report took an “off with their head” approach to his profession, even though coroners generally do “a really good job with what they have.”

Murphy also made it clear that coroner systems come in many different forms, including those that insulate coroners from political pressure and the influence of law enforcement. In Clark County, for example, the coroner is appointed by the seven-member county commission, a process that mirrors the way many counties select their chief medical examiners.

In his view, laypeople are entirely capable of running a medical operation, noting that many hospitals are helmed by chief administrators who are more knowledgeable about finance than anatomy. “That model works well in hospitals all over the United States,” he said.

Massachusetts: An Office In Turmoil

Hobbled by mismanagement and chronic underfunding, the state’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner has spent much of the last decade mired in disarray, its woes detailed in a succession of audits and reports .

At times, Massachusetts’ forensic pathologists have toiled in disturbingly decrepit conditions. The National Association of Medical Examiners, a nonprofit body that inspects and accredits morgues, issued a blistering inspection report in 2000 identifying more than 50 significant problems at the agency’s facilities. At one morgue, since shuttered, doctors were collecting blood, bile and other bodily fluids in 5-gallon buckets and pumping them back into corpses because a septic system had collapsed, making it impossible to wash the fluids down the drain.

“It was a terrible facility — the worst I’ve ever seen,” remembered the inspector, Dr. John E. Pless, an Indiana forensic pathologist, who said the practice posed “an obvious health risk.”

Pless also concluded the office would need $10 million annually in additional funds to do its job properly.

The budget has nearly tripled in the past decade, but even today, it is $3 million below the threshold set by Pless 10 years ago. The agency has never regained its NAME accreditation.

The office has struggled with the most basic of tasks. In 2003, it mixed up the bodies of two women severely burned in a Gloucester house fire. The blaze killed Ann Goyette and injured her friend, Susan Anderson. But when Goyette’s body was delivered to the morgue, a doctor mistakenly wrote the name Susan Anderson on the death certificate. In fact, Anderson, comatose, swathed in bandages and surrounded by an oxygen tent, was lying in a bed in Massachusetts General Hospital.

By the time the mistake was uncovered, the agency had cremated Goyette’s body, further upsetting her already distraught family. “How could the ball be dropped so many times?” asked Goyette’s brother, Scott Arnold, who unsuccessfully sued the state over the snafu.

A comparison of data from the nation’s 17 statewide medical examiner systems – including Washington, D.C. — shows that Massachusetts’ autopsy rate has fluctuated wildly in recent years. In 2004, it had the second-lowest autopsy rate among statewide systems, doing just three autopsies for every 100 deaths. Washington, D.C., the system with the highest rate, performed about 20 autopsies for every 100 deaths that year.

By 2006, under the direction of an ambitious new chief, the medical examiner’s office was taking on far more cases and had brought its autopsy rate up to the average level for statewide systems — to about six per 100. But the agency didn’t have the personnel or facilities to handle the increase. Unrefrigerated bodies began piling up in the hallways, and blunders mounted.

John Grossman, who oversees the medical examiner’s operations as the state’s Undersecretary for Forensic Science and Technology, said the agency has made improvements since then. It has hired new medical staffers and developed safeguards against errors.

“I know we’ve made great strides in the last three years, putting systems in place so that the office is not on the verge of collapse, creating a culture where the doctors feel supported,” Grossman said.

But the state also has scaled back its operations since 2007, slashing the number of autopsies its physicians perform by almost 25 percent to about 2,700 per year.

“In a world of unlimited resources, we’d like to do more autopsies, but we don’t live in a world of unlimited resources,” Grossman said.

A Lack of Qualifications

Despite the ubiquity of forensic pathologists in pop culture, the field has little appeal to most medical school graduates.

To become certified by the American Board of Pathology , doctors must receive an extra year of training in autopsies at a coroner’s or medical examiner’s office and pass a one-day exam. In addition, forensic pathologists are typically paid less than doctors in other specialties.

By most estimates the United States has only 400 to 500 full-time forensic pathologists. It’s a tiny cadre of professionals for a country where roughly 2.5 million people die every year.

Partially because of the shortage of qualified practitioners, many of the nation’s busiest coroner and medical examiner offices employ physicians who are not certified.

A survey of more than 60 of the nation’s largest medical examiner and coroner offices by ProPublica, PBS “Frontline” and NPR found 105 doctors who have not passed the exam — or more than 1 in 5 doctors on their full-time and part-time staffs.

Some have recently completed their training and have not had a chance to take the test, which is offered once a year. Others are long-time practitioners who have no plans to become certified.

But in numerous cases, the doctors are not certified because they have failed their exams.

The Arkansas State Medical Examiner’s Office employs two forensic pathologists who have flunked their exams multiple times, according to Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Charles Kokes. He described certification as a “personal goal” and said the doctors had no plans to take the test again.

In Kentucky, Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Tracey Corey acknowledged that the state employs a doctor who is not even eligible to take the forensic pathology test because she failed the anatomic pathology exam, which is a prerequisite. “I’m comfortable having her work because I know her competence,” Corey said.

The sheriff-coroner in Orange County, Calif., contracts with Juguilon Medical Corporation to provide autopsies. One of the company’s doctors has failed the certification exam at least five times, acknowledged Dr. Anthony Juguilon, the company’s chief, in an e-mail.

Some experts put little weight on board certification, but many leaders in the field say it’s a critical element — that you can’t raise the overall quality of death investigation unless the people who do autopsy work are subject to consistent professional standards.

“What does it mean? It means that they have not demonstrated they have minimum knowledge of the field,” said Dr. Vincent Di Maio, the former chief medical examiner for Bexar County, Texas. “And these people get hired.”

‘I Think We Miss Murders’

Lack of resources has forced Oklahoma to engage in a risky brand of triage.

The state’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner has been without its top doctor for nearly a year. Three of its nine slots for forensic pathologists are empty.

Its remaining six doctors handle overwhelming caseloads. Most did between 300 and 400 autopsies last year, said Timothy Dwyer, the state’s chief investigator. One did more than 500 — double the maximum number recommended by the National Association of Medical Examiners.

Because of the grueling pace, the state has had to impose limits on the types of cases it investigates: Oklahoma typically does not autopsy possible suicides or alleged murder-suicides. In most instances, it does not autopsy people age 40 or older who die of unexplained causes.

“If we did an autopsy on every suicide, it would be all consuming, as with drug overdoses,” said Cherokee Ballard, the office’s chief administrator. “With suicides, we don’t autopsy most them because it’s an obvious cause of death.”

But experts called Oklahoma’s practices alarming. A savvy criminal can make a murder look like a suicide, said Dr. Robert Bux, a forensic pathologist who serves as coroner for El Paso County, Colo.

“The only way you’re going to be able to sort it out, from my standpoint, is to do a complete autopsy,” Bux said.

“I’ve had a lot of suicide cases they didn’t autopsy,” added Kyle Eastridge, a former homicide detective with the Oklahoma City Police Department and the Oklahoma State Police. “I don’t think that every suicide is a murder, but I think we miss murders.”

In the absence of forensic findings, families sometimes are left to forage obsessively for clues about what became of their loved ones.

When a bullet shattered the face of 17-year-old Carissa Holliday and left her dead in a trailer outside of Tulsa, no doctor ever autopsied her body.

Instead, a forensic pathologist looked at her wound and filled vials with blood and fluid from her eyeballs, screening them for drugs and alcohol. Two days after her death, before the lab tests had even come back, the doctor ruled her death a suicide, records show.

Holliday’s mother, Andrea, didn’t believe the ruling — Carissa left no suicide note, and the pathologist’s report did not address potential clues such as whether there was gunshot residue on her hands.

“For a year and a half, I dug and investigated and got clues and witnesses to prove that she didn’t kill herself,” said Andrea Holliday, who wrote a self-published account of her daughter’s final hours titled Never Forgotten.

The medical examiner has not reopened Carissa Holliday’s case, and the official ruling on her death remains unchanged.

In 2009, NAME yanked Oklahoma’s accreditation, in part because of its failure to autopsy suspected suicide and homicide cases.

Fierro, the Virginia forensic pathologist, called Oklahoma’s decision not to look carefully into unexplained deaths of residents over 40 a mistake. Forensic pathologists have been critical in a range of investigations stretching beyond criminal justice, from identifying defective cribs to tracking the spread of infectious diseases. They play a crucial role in mapping public health trends, she said.

“If you want to improve the quality of people’s lives, then we need to know what it is that causes them to be ill, sick or injured so that they can prolong their life,” Fierro said.

Even at some of the nation’s more robust death investigation units, staffers worry that they do too few autopsies to fulfill their watchdog role.

The Los Angeles County Department of Coroner looks into a comparatively large portion of deaths, roughly one in three each year, said Craig Harvey, the chief death investigator. Yet he would like to do more.

“I would love to have the staff to respond to every nursing home death. They’re fraught with potential misses,” Harvey said. “But if anything was to go wrong in those facilities, unless somebody says something, there’s a good chance the case will pass through the system without ever being seen by the coroner.”

The Price of Reform

The National Academy of Sciences has mapped out a plan to improve troubled coroner and medical examiner operations.

In its 2009 report, the academy called for the creation of uniform federal standards for death investigation and recommended making certification mandatory for doctors working in the field of forensic pathology.

So far, however, those suggestions have made little headway in Washington.

Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., recently introduced legislation aimed at upgrading the quality of forensic evidence, but his bill would impose no new requirements on the doctors at the center of death investigations. Instead, it would establish a committee to examine how to ensure that qualified practitioners are doing autopsy work.

Many of the academy’s proposals would take money — money to educate doctors, to hire more of them and to construct up-to-date facilities.

It’s not an overwhelming amount. DiMaio, the former Bexar County medical examiner, estimated that the price of a good medical examiner’s office is about $2.50 per person per year, “which is probably less than what you pay for a Coca-Cola in a movie theater.”

So far, however, even that is a price many communities have been unwilling to pay. Oklahoma, for example, spends about one-third less each year on its medical examiner than DiMaio’s formula suggests it should.

Dr. Victor Weedn, the Maryland assistant medical examiner, said basic misunderstandings about the significance of death investigation have made it a hard sell.

“It’s difficult for people to spend money on medical examiner systems,” Weedn said. “They see it often as wasting money on the dead, without realizing that everything that is done in a medical examiner office, or a coroner office, is truly done for the living. We try to protect society. We look for deaths that are premature, or that should not have happened, so that we can go forth and correct those errors in society.”

ProPublica Deputy Editor of News Applications Krista Kjellman-Schmidt, Director of Computer-Assisted Reporting Jennifer LaFleur, Director of Research Lisa Schwartz and reporter Ryan Gabrielson of the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley contributed to this report.

Additional research was provided by Liz Day, Sydney Lupkin, Kitty Bennett, Sheelagh McNeill and Ryan Knutson of ProPublica, Jackie Bennion of PBS “Frontline,” and Barbara Van Woerkom of NPR.

Correction:

An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified David Balash as a doctor. Due to a data collection error, that earlier version cited Utah as the jurisdiction with the highest 2004 autopsy rate in our analysis. In fact, Washington, D.C., has the highest rate.