By Steven M. S. Kurtz, Ph.D., ABPP

Youth with AD/HD often experience problems making and keeping friends. The summer can be a great time to work on improving social skills. Common sense and research teach us that each of the parts of the AD/HD triad—inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity—may make social skills difficult. Inattentive youngsters are less likely to pay attention to social cues and the subtleties of interactions. For example, they might not pick up that a friend is getting bored and wants to move on to something else, or that the friend knows different rules for a game and the AD/HD child rigidly sticks to the rules he knows. Another common missed cue involves getting into someone else’s personal space.

Since social skills such as negotiating, accepting the choices of others, and complimenting others appear not to be inherently reinforcing for AH/HD youngsters as for their non-AD/HD peers, these skills need to be practiced often and throughout the entire year. The summer is a great opportunity for parents to prompt, monitor, and reinforce these skills since they tend to be with their children a lot more.

Hyperactive and impulsive children may jump to conclusions, make quick negative judgments about the intentions of others, or over-react to situations. If the theories of Barkley and others are correct, then these children have deficits and delays in inhibiting responses. To the extent that so many children with AD/HD also have very significant levels of oppositionality, or anxiety, it’s easy to understand why making and keeping friends may be so tough for them. Anxiety, that is unrealistic worries and rigidity about things being a certain way, can be an incendiary mix with AD/HD symptoms. Picture this: the worried, anxious and rigid child, who also has AD/HD, would be even more likely to be bossy, demanding, and impulsive, in interactions with peers because he needs to protect his little "islands" of worry. For example, an AD/HD and anxious child who is worried about his toys not being moved around at all, or his Lego-sculpture not being changed at all, is more prone to an impulsive, demanding, even aggressive stop as his buddy approaches the toys in question. He is also less likely to attend to the friend’s confusion and hurt at being rebuffed on a playdate. Similarly, the oppositional child—the child who blames others, denies responsibility, is tough, or seeks revenge—who also has AD/HD, is at risk with peers because either set of traits is off-putting. This might be the child who not only impulsively cheats, but then denies it, blames the friend, punches or teases him, and then storms off. Obviously these combined diagnostic situations put children at extra risk for social problems.

The research on social skills treatments for children with AD/HD has been incredibly humbling to professionals who work on developing such treatments. While you can easily find many therapists and commercial groups advertising that they provide social skills training, there is little research evidence to support the notion that children with AD/HD will learn social skills in a clinic that will carry over to their real-life settings. This notion of generalization is the bugaboo of behavioral research. Therefore it is quite reasonable to assume that social skills training in a child’s real-life settings will be more effective than in a clinic. Research has yet to consistently bear this out, but clinic-based social skills results have been disappointing with only a few exceptions.

Right time, right place

Certain activities are more apt than others to to pull the best from your child. Play to your child’s strengths by choosing an activity at which your child succeeds to do with someone else. The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior! So stick with activities your child does well and in which he or she may be able to be a leader demonstrating competencies for other children to learn from. One young boy I knew used to take a child fishing with him, where he could appropriately be "in charge" showing the peer what to do. Bob Brooks calls these abilities the "islands of competence" and they provide a great starting point. Let the child who is great at woodworking help his buddy build an easy project, such as a birdhouse. Let the child who is super at cooking make dinner for the family and a friend. But if your child is prone to being bossy at these activities, choose something else. That’s what we mean by playing to their strengths! This way prosocial skills such as sharing, can be reinforced, especially if you, as the parent, are there to point out how well the children are doing.

The right playmate

Invite a playmate with whom your child does well in one-to-one outings. Stack the deck in his or her favor by inviting someone who will be a good role model for social skills. Start small as these interactions are more containable. Starting small is relative and may mean just an hour or so the first time with a new child rather than all day long. Or if you are doing a sleepover, have the child picked up shortly after breakfast rather than having the playdate going on too long. Maybe just a movie is enough and a sleepover may be pushing your luck.

Define the skills

Be clear about which social skill you are targeting. Behavioral researchers stress the importance of using well-defined positive, prosocial, behaviors, such as sharing, negotiating, and complimenting, to work on or target, rather than either vague goals such as "be nice" or negative goals such as "not being mean." It’s always more fun to work for the presence of a positive goal, rather than the absence of a negative one. So, begin by sitting down with your child and tell him that you are going to be on the lookout—to "catch him being good"—at specific behaviors such as sharing or complimenting.

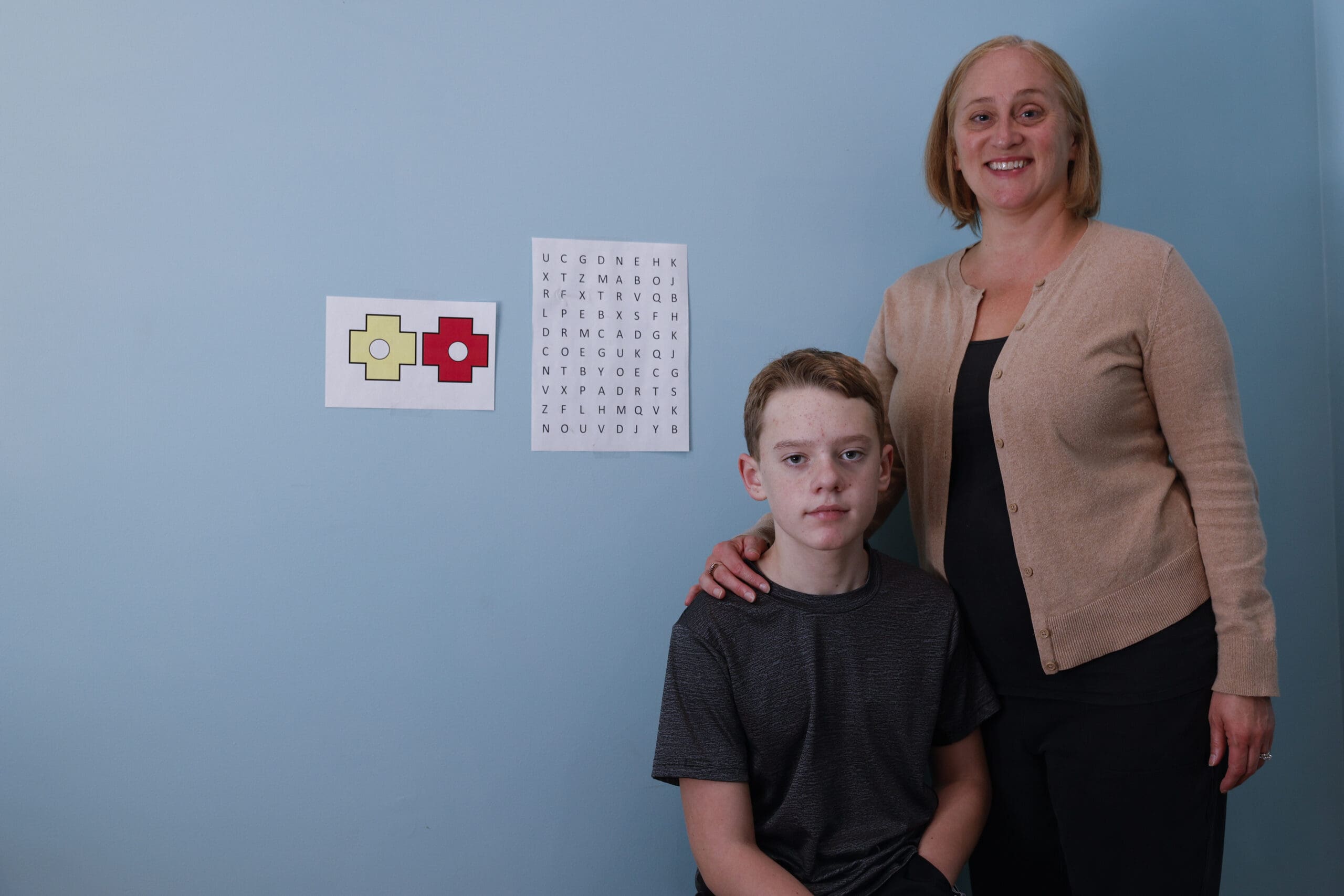

Behavioral contracts and rewards

Behavioral "report cards" with rewards continue to be one of the mainstays of behavioral interventions for children with AD/HD. These behavioral report cards set children up for success by telling them exactly what they need to do, when they need to do it, and provide that extra incentive to strive for the goal. The thought and the hope is that once the child is engaging in good social skills, such as being patient and following game rules that the naturally occurring reward of social approval by peers will take over to reinforce the behavior and keep it going. But in the meantime, we need to provide "reward" incentives to help the children do the skill in the first place. Behavioral contracts often take the form of a chart with a certain number of points to be earned and then traded in for rewards. Rewards vary greatly from parent to parent and child to child. Research does not suggest that any one type of reward is superior to another. Many professionals push for fun, immediate, easy-to-use behavior rewards, rather than money, food or costly toys. Common rewards are things like staying up 15 minutes later, taking a bubble bath, extra story time, renting a video, or playing a game you don’t usually play with your child.

Be proactive

Researchers are investigating the possibility that children with AD/HD may not generalize well. During the summer, parents can protect against this by creating situations for their children with AD/HD to practice the desired social skills in as many situations and with as many different children as is possible. Situations may vary from your house to the other child’s house, the playground, at a picnic, or at the bowling alley. Good behavior therapists practice skills with children in different settings by prompting the behavior—reminding the child what skills you want to see them using, then monitoring the behavior—being on the lookout to "catch the child" doing the desired behavior, and then reinforcing the behavior with labeled praise, such as "Teddy, I love the way you let Nate pick the first game. That’s a great way to keep friends." If you are using a behavior report card, as suggested above, then that would be a great time to put a mark down showing that the behavior happened. Now your child knows he is even closer to the behavior reward!

Coordinate the coaches

Make sure that all your child’s summer "coaches" know exactly what social skills you are working on. That way each one of them can be on the lookout to prompt, notice, and reinforce the behaviors you are targeting. Include camp counselors, baby sitters, grandparents, and anyone who can help. It’s best when everyone is using the same words and focusing on the same desired behaviors.

By following these guidelines, you can be your child’s "summer school" teacher for social skills. It’s a great time to practice real-life social skills, in real-life settings, with their real-life peers and increase the chances that these gains will continue as school starts again in the fall.

References

Pfiffner, L. J., & McBurnett, K. (1997). Social Skills Training with Parent Generalization: Treatment Effects for Children with Attention Deficit Disorder. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 65, 749–757.

Barkley, R. A. (1997). ADHD and the Nature of Self-Control. NY: Guilford Press

Brooks, R. B. & Goldstein, S. (2001). Raising Resilient Children. NY: McGraw Hill

The NYU Child Study Center is dedicated to the understanding, prevention, and treatment of child and mental health problems. For more information visit aboutourkids.org.