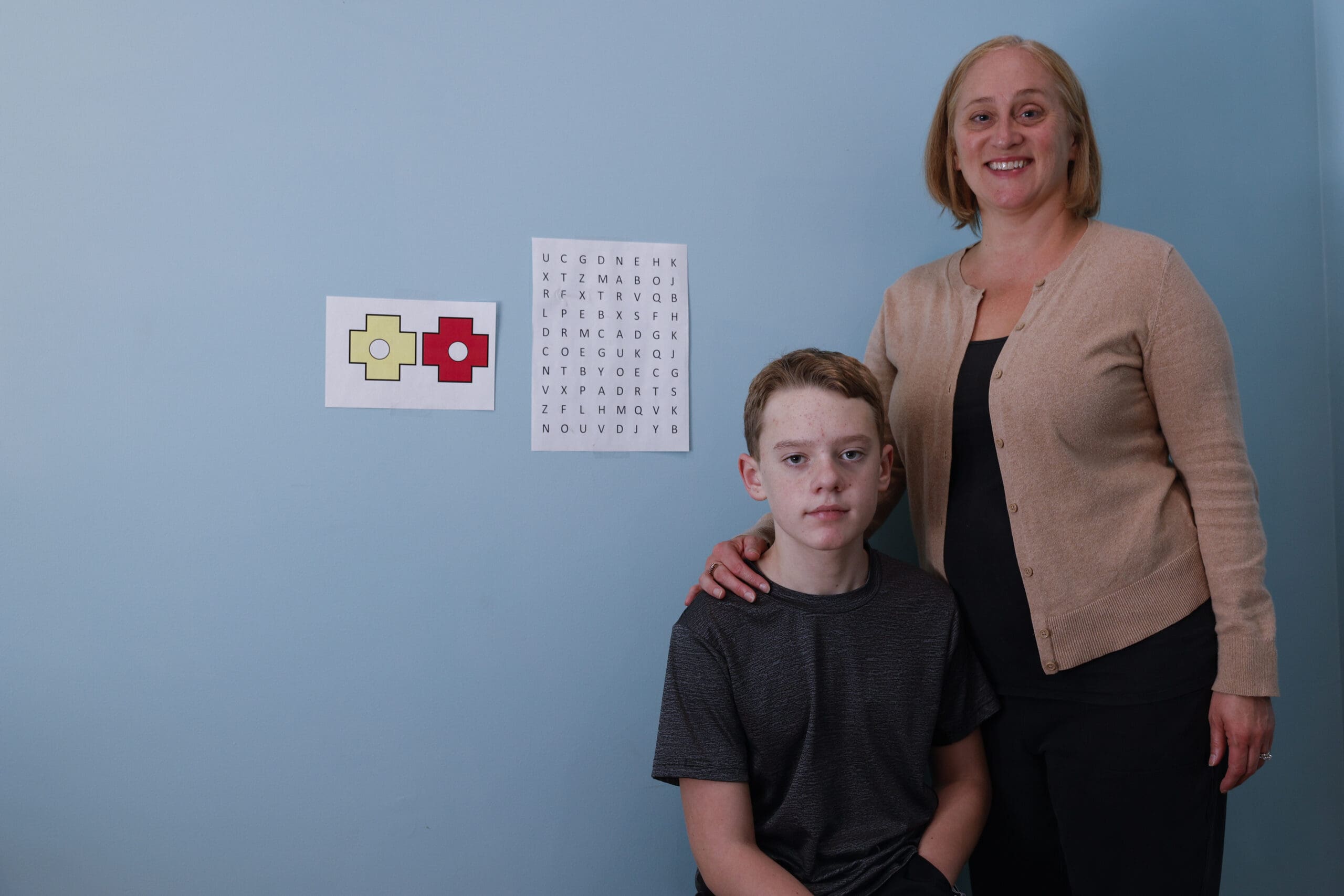

Although it may feel like your defiant child hates you, that’s usually far from the truthBy James Lehman, MSW

If you’re the parent of a defiant child, you’ve probably wondered what makes him so angry at life—and angry at you. With the school year approaching, are you gearing up for another difficult year with your child, just hoping that he’ll make it through—and that you’ll be able to manage without falling apart? Realize that it doesn’t have to be a daily battle of wills once you understand what’s actually going on in your child’s head. Here, James Lehman MSW breaks down some of your child’s thinking on a typical school day.

It’s another day and another battle. The alarm goes off, and your child yells, “School sucks. Why do I have to go? It’s not fair!” He hasn’t done his homework (again) because, as he sees it, the teacher didn’t explain the assignment to him. He adds, “Besides, my teacher is a jerk, and she doesn’t like me, anyway.” You find yourself yelling, “Hurry, you’re going to miss the bus,” but instead of getting ready, now your child is dragging his feet and shouting, “Leave me alone!” As on countless other days, he misses the bus and starts pleading with you for a ride to school, saying, “You don’t want me to be late, do you, Mom?” Before he gets out of the car, he reacts to your speech about trying harder tomorrow by screaming, “All right, get off my back. Why are you always yelling at me?” and slams the door. At school, he gravitates to the wrong group of friends and goofs off in class; even worse, he talks back to the teacher instead of paying attention. When he comes home in the afternoon, he grunts at you before getting onto his video games (you think they’re way too violent, but he loves them) listens to music which you find offensive, and talks openly about admiring people who are crooks and criminals. That night, you know your child is probably going to stay up until all hours playing more of those video games you can’t stand, but you’re so tired of fighting with him that you just fall into bed exhausted.

As a parent, you live this kind of situation every day when you have a defiant or “difficult” kid, but have you ever wondered what’s going on in your child’s head when he’s fighting with you? Although it may feel like he hates you, that’s usually far from the truth. Rather, kids get caught up in a long chain of what we call “thinking errors” that can tangle up their emotions and behavior—and make no mistake, unless they get help, thinking errors can dominate a person’s thought processes throughout their entire lives.

Here’s how some of the thinking errors used by the child above break down—and what you can do to challenge these faulty ways of thinking in your own child.

Thinking Error #1: “School sucks. Why do I have to go? It’s not fair.”

What It Means: One of the thinking errors this child is using is called “Injustice.” Realize that many kids see things as being unfair. The danger is that once they label something as “not fair” they feel like they don’t have to follow the rules or honor your expectations. This is pretty common in our society. If you’re on the turnpike and the speed limit is fifty-five miles an hour, you’ll see many people going sixty-five and seventy. It’s because they think fifty-five miles an hour isn’t fair—and once they decide it’s not fair, then in their minds, the speed limit rules don’t apply to them.

We all use thinking errors to justify doing things we know are risky or unhealthy. People use errors every day to gamble, lie, steal and cheat—or simply to justify having that second helping of pie. The problem is when kids use thinking errors to avoid taking responsibility. When they do this, they’re not realistically preparing for the adult world which awaits them. Remember, it’s not what the thinking error does—it’s what the thinking error justifies or permits.

What You Can Do: It’s important for you as a parent to challenge the error in thinking in a non-confrontational way. One thing the mother in our example could have said was, “You know school is your responsibility. If you don’t get up, you’re going to get an earlier bedtime. And it looks to me like you need to get more rest so you can get up on time.”

Thinking Error #2: “The Teacher is a jerk—and she hates me.”

What It Means: When a child says something like this, he’s using a thinking error called “The Victim Stance”. Some kids see themselves as victims all the time and in almost every situation. What they’re doing is trying to reject the idea that they’re responsible for anything. You’ll ask them a question and they’ve always got a sad story. Part of that sad story is who they blame for not meeting their responsibilities. That’s because when you’re a victim, you blame other people. So these kids blame the teacher, they blame you, or they blame somebody else—and what they learn is if they stick to their story long enough, they won’t be held accountable.

What I try to tell parents is that there is a sad story, and then there’s a behavior story. The sad story is your child playing the victim; the behavior story is what your child did to other people or to property. And as parents, we always have to focus on the behavior story. Every child has to be responsible for the behavior story, not the sad story. Don’t forget, when kids see themselves as victims, that gives them the justification they need to not meet their responsibilities. If you’re a victim, they reason, you shouldn’t have to do anything you don’t want to do. And focusing on the sad story somehow supports their right not to meet responsibilities.

What You Can Do: When your child adopts the Victim Stance, what he needs to be hearing from you is, “You’re not a victim. You’re responsible for your actions.” In this case, the parent could also say, “It sounds like you’re blaming your teacher for not having your homework done. But you’re the homework-doer—that’s your responsibility. And it’s not your teacher’s job to get along with you; it’s your job to get along with your teacher.”

Thinking Error #3: “You don’t want me to be late for school, do you?”

What It Means: This is the thinking error I call “Concrete Transactions”. The Concrete Transactions mode is a way of thinking about things in which relationships with people in authority are simply vehicles your child uses to get around the rules. What he is saying is, “I’m your friend, and since I’m your friend, you’re going to help me get away with things—or help me get things I’m not entitled to.” So in your child’s mind, relationships are designed to help him get around rules, expectations and responsibilities. In other words, he thinks, “If I have a relationship with you, then you won’t make me follow the rules. You’re going to let me stay up past bedtime and sleep late in the morning.” So to your child, rules and the rights of others are seen as obstacles in relationships. The use of “Concrete Transactions” is designed to make you remove those obstacles instead of helping your child develop the problem solving skills he needs to manage the challenges he faces.

Know that if you’re in this kind of relationship with your child, you’re not really a person—you’re a role. Simply put, your child will treat you the right way as long as you stay in your role. If you try to leave it and be more responsible and hold your child accountable, you will often get a very nasty reaction.

By the way, whenever I hear parents say they want to be their kid’s friend, I become concerned. If parents want a friend, they should seek it outside of the home or get a puppy. These kids don’t need their parents to be their friends. They need direction, limits, coaching, teaching and structure. Look at it this way: if you define friendship as a mutual relationship where two people really try to take care of each other, then the best way to be your child’s friend is by being an effective parent.

What You Can Do: It’s important that children face the true consequences of their behavior. And when an authority figure such as a parent or teacher lets them off the hook, it doesn’t matter what they say to the child to justify it. As far as the child’s concerned, it works: He won.

In the example above, I would suggest that if possible, and if it’s safe, the mother should leave her child at home. Most kids complain about going to school, but they have no place else to go. And remember, if you leave him home, take the video game, cable box and computer control panel with you in the trunk of your car—and don’t forget his cell phone.

Thinking Error #4: “This video game is cool. Mom doesn’t know what she’s talking about—she’s so uptight.”

What It Means: This child is using a thinking error called “Pride in Negativity”. Defiant kids often take a lot of pride in their knowledge of unhealthy, secretive things. They have a fascination with negative role models because they see them as being powerful. These kids might hint at having a secretive, negative life. They may also take great pride in telling you that they know about different drugs and where to get them, and in their knowledge of crime—and how to shoplift and steal.

Kids who have low self esteem and no way to solve problems will gravitate towards peers who don’t expect anything out of them. Those kids in general will see negative behavior as a solution to their problem. In the end, “Pride in Negativity” means self esteem and identity from negativity.

What You Can Do: One of the big mistakes parents make is to argue with their kids about the negative things their child is fascinated with. But fighting about those issues only gives the child more power. I personally think parents should have a structure in their home that forbids the games they’re not comfortable with. You should also really ignore any Pride in Negativity statements by saying, “Look, I’m not interested in that stuff,” and then walk away. In other words, give it no power. Remember, if you show your child that certain behaviors have power over you, those behaviors are going to be repeated. Conversely, behaviors that have no power over you will diminish.

It’s important to remember that kids believe in the thinking errors they’re using. As a parent, I believe to be overly confrontational is not the way to go. What’s preferred is a corrective response that challenges or refutes the thinking error. After all, these errors are part of every day life. You’ll find that people use them all the time. In fact, I find myself using thinking errors, and you might find yourself using them, too. But here’s the risk for your child: kids, and especially teens, use these errors in thinking to avoid doing things that are difficult for them, and that’s what makes them dangerous. Remember, adolescence is one of the most critical times in your child’s development for them to learn how to solve life’s problems—not avoid them by using excuses, manipulation or lies.

James Lehman, MSW, the creator of Total Transformation program, and EmpoweringParents.com. “A Day in the Mind of Your Defiant Child” by James Lehman, is reprinted with permission from EmpoweringParents.com. EmpoweringParents.com is an online community and resource for parents offering practical content that addresses child behavior problems.